Queen Elizabeth II’s reign is an age of service almost unprecedented in the monarchical record books. In her Platinum Jubilee year, the Queen’s traditional Commonwealth Day message reiterated the vow of dedication to her peoples, first made in Cape Town on her 21st birthday. Yet on the cusp of her 97th year, stricken with Covid and quipping to diplomats on her growing physical limitations, we must seriously consider the monarchy’s future, post-Elizabeth II.

The generational divide

The question of the Queen’s succession is nothing new, but as historian Helen Thompson observes, there is a stasis in the monarchy that has arisen by dint of her remarkable longevity. Elizabeth II is almost universally admired, yet the most recent YouGov poll (November 2021) displayed much greater ambivalence on the subject of whether Prince Charles will make a good king. Participants were equally split: one third in favour, against, and unsure.

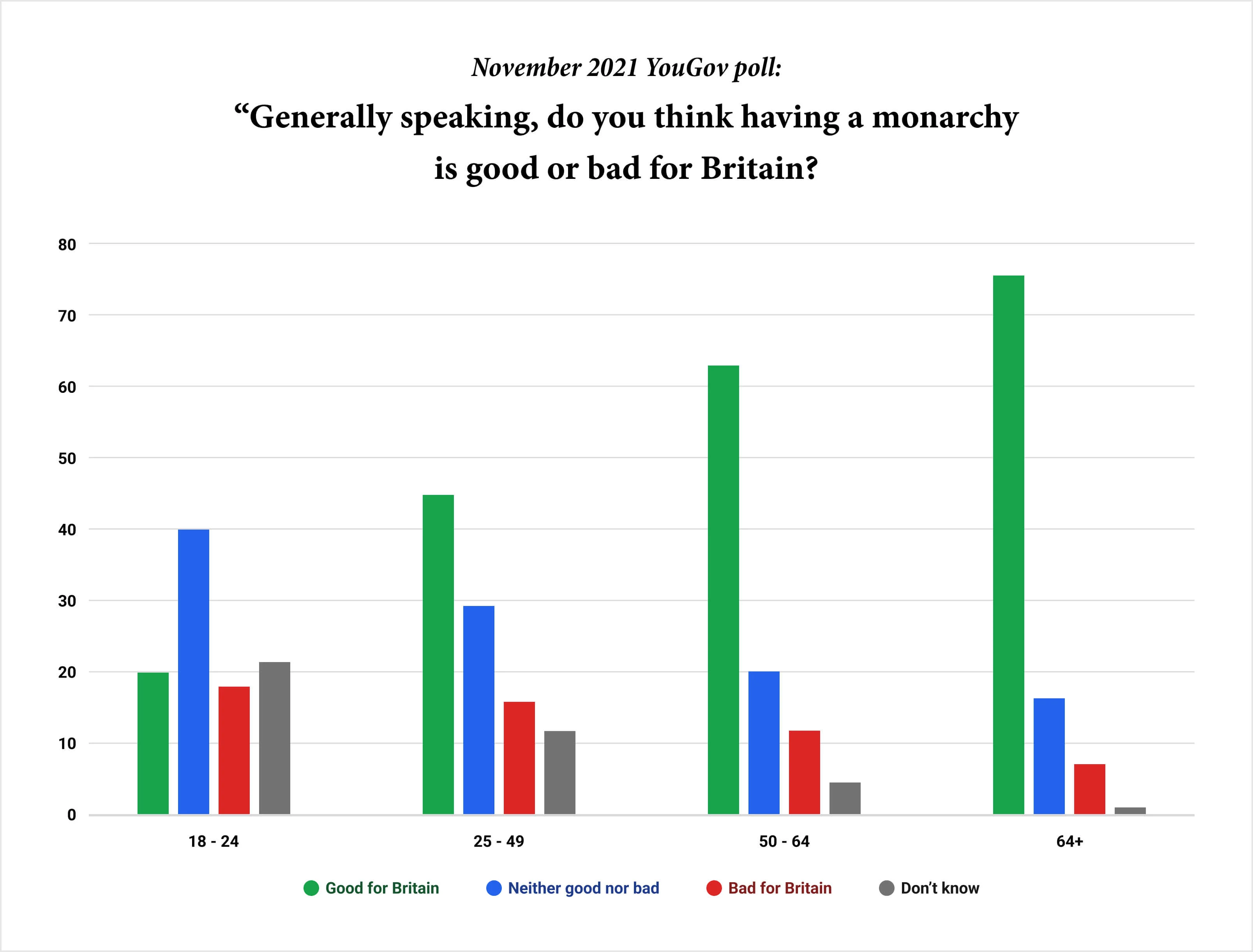

This itself masks a stark age divide. Among respondents aged 18 to 24 and 25 to 49, only 17% and 29% support Charles’ succession, respectively. Most strikingly, only 20% of the 18-24 category have a positive view of the monarchy at all, compared to 54% across all ages of respondent. The full age breakdown is as follows:

Young people, it appears, view the Royal Family as an irrelevance and one can understand why. The Sovereign Grant that finances the Windsors is the largest of any monarchy worldwide: there are too many palaces, staff, and hangers-on. In an increasingly irreligious country, the sovereign’s role as Supreme Governor of the Church of England seems especially inaccessible for non-Anglican citizens. Media depictions – real and fictional – imbue the Royal Family in a culture which ranges from outdated stoicism at one end to moral repugnance at the other.

Two scandals have particularly hit the monarchy’s reputation: Prince Andrew’s alleged child sexual abuse, and the withdrawal of the Sussexes from royal life. The Duke of York’s 2019 Newsnight interview exposed the astonishing excess of his blue-blooded privilege: where befriending Jeffrey Epstein is a useful business opportunity. Andrew has been stripped of his titles but his recent settlement of the sex assault case with his purported, then-17-year-old victim, Virginia Guiffre, itself raises the question of how much of the bill will derive from the public purse. It speaks to the Royal Family’s rigidity that it sheltered Andrew - still the Queen’s choice to accompany her to Prince Philip’s recent memorial service - but failed to accommodate the outspoken, mixed-race Duchess of Sussex. Meghan Markle, who married Prince Harry in 2018, withdrew with her husband from royal duties and entitlements in 2020 (if continuing to profit, through vaunted interview slots, from the fallout). This was prompted by intense media scrutiny directed on the Duchess; mutual antagonism between Meghan and royal staff, including racism; and the couple’s feeling of confinement within the monarchy’s protocols. Younger generations particularly relate to her apparent maltreatment. Among Millennials, Meghan is the 6th most popular Windsor in YouGov’s autumn 2021 polling. For Baby Boomers, she is 14th: ahead only of Andrew (last in both). Evidently, if the Royal Family should continue to command legitimacy from its younger subjects, cultural and structural reform must start now.

After all, monarchy is an enduring symbol of our national story. Over two centuries, the Royal Family have lost their claim to infallibility but continue to command deep respect from their commitment to tradition, remembrance, and community. Their rituals serve to ground a “British” people with a shared set of ideals and conduct. In their vital charity work, senior royals champion causes that the state cannot reach, or where it would be improper for politicians to do so. The institution should certainly be streamlined – in the model of the “bicycle monarchies” of Scandinavia or the Netherlands – as Prince Charles himself has floated. At the end of the Cambridges’ recent Caribbean tour, Prince William conceded that he might never lead the Commonwealth. But total abolition would be a retrograde step that causes more problems than it solves. Through two world wars and an abdication crisis, the monarchy proved its capacity to adapt; it must now do so again.

National identity and public service

In his 1995 work, Banal Nationalism, Michael Billig spoke of monarchy as a semaphore for nationhood. The institution sits at the heart of many Britons’ day-to-day conception of their national identity and provides a model for behaviour, with the sovereign as head of state and the Anglican church. The Queen has provided a unifying salve for her citizens at challenging times. I think of the emotional reaction elicited by her characteristically stoic Easter address in the first 2020 lockdown, or the image of her seated alone at her husband’s funeral, abiding by pandemic restrictions while their architect set about flaunting them in the Number 10 garden. In recent weeks, it was no coincidence that the Queen chose a yellow and blue floral display as the backdrop to her audience with Canada’s Prime Minister. In the 21st century, an unelected monarchy based on bloodline may seem an irrational concept, but if it is bound with concepts of duty and service in the name of one’s country and its allies – in the Queen’s example – it will continue to prove an anchoring presence.

Beyond the sovereign, many senior royals demonstrate the “soft power” role which confirms their relevance to younger generations. The Royal Family can secure vital public attention for non-political causes, beyond the realm of the state, by virtue of their status. This ranges from the Duchess of Cambridge’s work on youth mental health to the Duke of Sussex’s Invictus Games for injured and recovering veterans. Princess Anne alone is patron to over 300 charitable organisations such as the Carers Trust, The Royal College of Midwives, and Save the Children UK. Prince Edward spent his 57th birthday not at an extravagant gathering but cooking with his wife for a homelessness charity. Lamentably, this aspect of unstinting duty is marginalised, given mainstream media’s focus on scandal or the sovereign herself. The monarchy can circumvent this by embracing non-conventional media forms; for instance, Prince William has appeared on podcasts to discuss his experience of depression. Most senior royals now detail their packed schedules on Facebook and Instagram, which suggest that the mystical distance between monarchy and public is nothing but fiction.

The streamlined solution

It is difficult for the Royal Family to promote this positive story when, for an institution funded and legitimated by the public, model conduct must be the default. But this problem can be alleviated after Elizabeth’s reign through a streamlining of the institution. The Dutch royal family, the Oranjes, are a case study for a more accessible and less expensive alternative. According to a Prospect magazine study, the Oranjes have 5 royal estates to the Windsors’ 23; 300 household staff compared to 2,500; and cost the Netherlands £39m annually to Britain’s £82m. The heir-apparent, Catharina-Amalia, rejected a £2m bequest for her 18th birthday to embrace a normal young adulthood. Queen Beatrix retired at age 75, allowing for a controlled transition to her son, while Queen Elizabeth’s stolidness in ruling out abdication brings uncertainty to the life of both Charles, who could conceivably succeed her in his eighties, and William. Our monarchy is ahead of the Oranjes in paying income tax, or opening palaces to create revenue for charity. But Joris Luyendijk writes of the Dutch conception of the Windsors as uncaring: shielded by tradition and a swollen court.

The post-Elizabethan monarchy can find a middle ground between out-of-touch, bloated irrelevance, and outright abolition. Indeed, while many young people would prefer an elected head of state, the ramifications of this are surely as unpalatable as the status quo. What powers would be enumerated to the new “President”? How would they conflict with those of the existing Prime Minister, or the constitutional supremacy of parliament? Our monarchy has evolved to an innocuous political position: the Queen last intervened in party politics in 1963, to select Lord Home as Prime Minister. She has since served as no more than a sounding board for Prime Ministers, versed in events through her red boxes. And how would we set abolition in motion? Any agreement that is not by mutual consent – for instance, a referendum – would risk exacerbating the forces that threaten to split the nations of the United Kingdom.

Admittedly, in the aftermath of the Cambridges’ tour of Caribbean Commonwealth countries, scaling down must include the right to self-determination in the 14 overseas nations that recognise Elizabeth II as head of state. Cynthia Barrow-Giles, Professor at the University of the West Indies, described the trip as ‘disturbingly self-serving’. Indeed, the tour will be remembered for photo opportunities redolent of a colonial age, or a missed opportunity for William and Kate to express regret for the Royal Family’s historic links to slavery, rather than its “soft power” engagement. Despite the Cambridges’ efforts, nations like Jamaica seem primed to follow the example of Barbados in November 2021 and abolish the monarchy. Nonetheless, this is a constitutional question for Commonwealth countries with likely differing opinions to decide on their own terms. Total abolition should not be imposed by the British metropole, precipitating constitutional upheaval from Nassau to Canberra.

In London, for sure, unilateral abolition would do more harm than good. There are more pressing British constitutional questions (the status of the House of Lords; the uneven devolution settlement; an anti-proportional electoral system) which surely should be tackled before a politically impotent but symbolically formidable monarchy.

In 2022, Elizabeth II stewards a towering edifice on foundations which, through inattention, have weakened over time. Her successors must emulate her finest qualities – immaculate duty and personal conduct – yet not at the expense of the monarchy’s emotional and cultural relevance. Young people in particular need a new narrative of how the Royal Family matters to them, and it can be found in its commitment to pioneering charitable causes and engagement in the societal mainstream. This must remain the focus of a smaller core of royals – Charles, Anne, Edward, William, and Catherine – willing to relinquish the lion’s share of their stately homes and vast Crown lands to reduce their distance from ordinary people, in the Continental European example. They must address the historical baggage associated with Commonwealth nations through more than charm offensives. There should be, as New Statesman columnist Philip Collins suggests, a mandatory retirement age of 65 for the sovereign. This would stabilise the succession and reflect the normal employment lifecycle. It would also prevent recurrent media frenzies whenever the monarch is taken ill. We may never escape the blend of deference and tabloid sensationalism that accompanies the Windsors, but perhaps if they appeared more like normal people, they would be treated less hysterically.

To prove its future relevance, the monarchy ‘must keep telling a story that engages people’, in the words of historian Alex von Tunzelmann. It has always adapted to contingency as it endures through time, as governments and social mores rise and fall. With Elizabeth II’s reign in its final chapter, another renewal is required.

Written by

Matt JeffordUniversity administrator and pub quiz enthusiast. I'm engrossed by current affairs, reading, tennis and food, and an expert in poor political predictions.

Weekly emails

Get more from Matt

The Fledger was born out of a deep-seated belief in the power of young voices. Get relevant views on topics you care about direct to your inbox each week.

Write at The Fledger

Disagree with Matt?

Have an article in mind? The Fledger is open to voices from all backgrounds. Get in touch and give your words flight.

Write the Contrast