Does war offer more community than peace ever could?

9 May 2023

9 May 2023

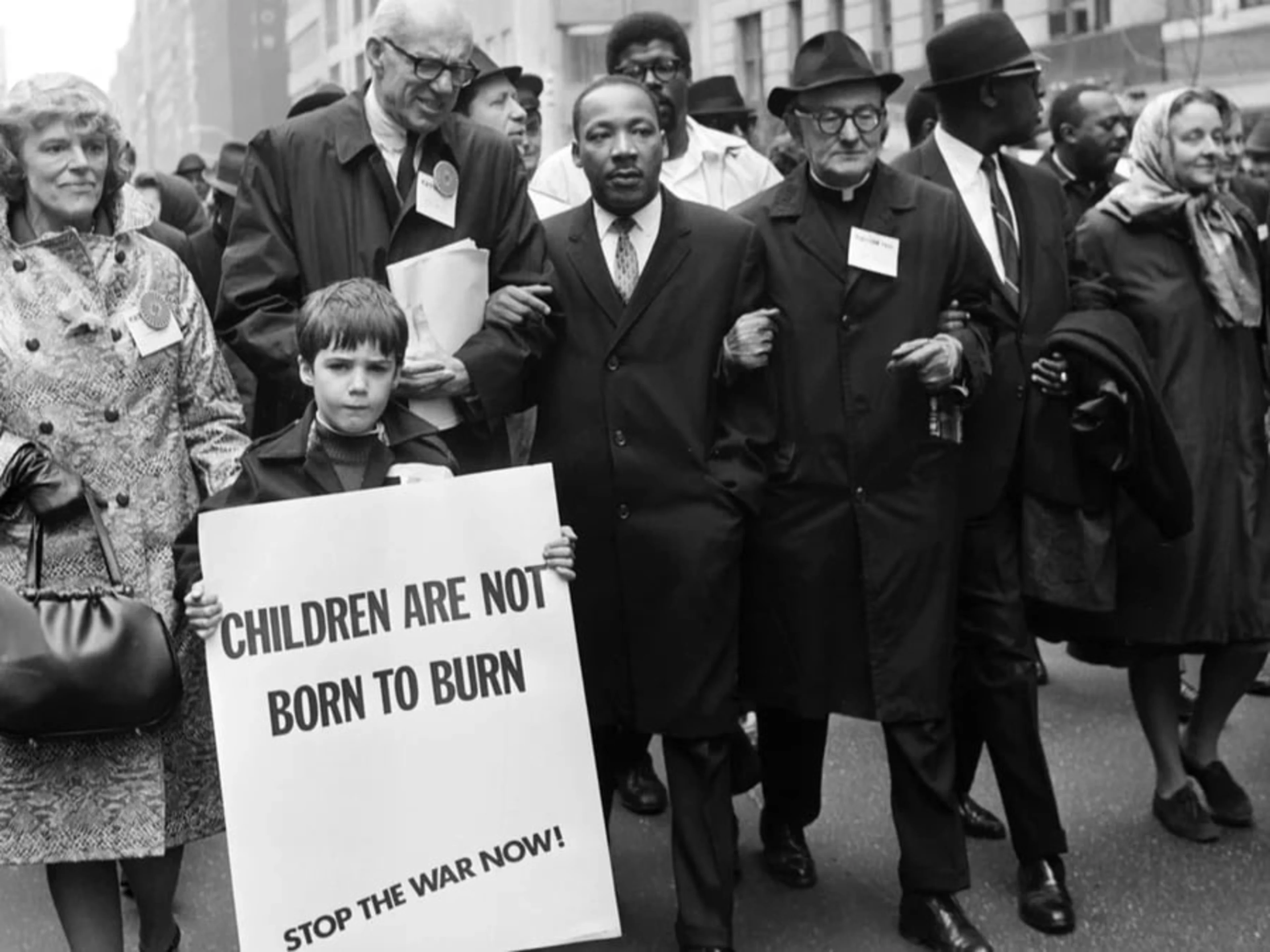

“We must see that peace represents a sweeter music, a cosmic melody, that is far superior to the discourse of war”

One of the many iconic quotes from one of the most iconic men in history, it poetically sums up the beauty of peacetime in a way that could only come from that man. But, while I agree with the overall sentiment, I believe that in these modern times, the issue it addresses has become far more complex, that maybe peace is no longer as harmonious and happy as it once was, and that war has given a few people different views.

War is a uniquely human fascination, nowhere else in the animal kingdom do species pit millions of their own kind against each other in a fight to the death, often in response to petty squabbles of the ruling elites. It destroys families, friendships, and souls. It can break apart entire nations, devastate communities and cause irreversible damage to the fabric of humanity. Some people have never known anything but war, while others still suffer its consequences decades later. Sons watch on as their fathers are shot to death by strangers, while mothers find their daughters blown apart by shrapnel. Parents outlive their children as boys and girls fight unknown people, in unknown lands for unknown reasons.

Yet humans have an astounding infatuation with war, thousands of books and songs have been written covering every conceivable gruesome detail. While one of the most popular genres of movies in the world is war films, they make billions at the box office, and actors are paid millions of pounds to star in them. History lessons are filled with statistics detailing every death, date and duration of wars fought since the birth of Christ. Poems and stories are echoed like gospel to children old enough to understand them as we grow up learning about every hero and every villain, every victory and every defeat, every conqueror, and every sadist.

This avid obsession with such a grotesque and abhorrent spectacle seems so peculiar, that on the surface it looks as if mankind has well and truly lost it, exorcized the morals which we as a species cherish and pride ourselves on, and locked them in a dark room never to be seen again. I’m sure you, like myself, have seen the videos of war online that display the horrible nature of conflict, yet keep us watching with a morbid fascination. Yet, if you can look past this vast network of information, and delve deeper while analysing real-world examples, this hobby of death begins to make sense.

The Siege of Sarajevo took place in Bosnia and Herzegovina during the Bosnian civil war of the 90s. It was a brutal and unrelenting siege lasting nearly 4 years, with civilians trapped between constant sniper fire and indiscriminate artillery. Listening to survivors’ stories though starts to paint a surprisingly glass-half-full kind of attitude towards it. Sebastien Junger is a war journalist who went to Sarajevo 20 years after the siege. In his book Tribe, he details how people would quietly hint about how much they actually missed the war and the people they had become during it. He talks about how his taxi driver on the way from the airport had been in a special army unit which slipped through enemy defences to help stranded soldiers, then he pointed to the dashboard and said, “Now look at me”.

Another survivor from the siege was Nidzara Ahmetasevic, a now well-regarded Bosnian journalist, she was only 17 at the time of war breaking out. Despite being hit by shrapnel in the opening few weeks, she seems to reminisce to Junger about her experience there in a very positive way. She remembers the way people in the siege worked together as a community to ensure their own and everyone else’s survival. They would eat meals together, sleep on the same floor together, and would constantly socialise in a way that Western societies today would never dream of. Six months into the siege, Ahmetasevic’s parents managed to get her evacuated to Italy, so she could properly recover from her previous injury. Despite the safety and life of almost luxury compared to living in war-torn Bosnia, she talks about how all she could think of while in Italy was a sense of loneliness and longing to get back, worried that her friends and family would die without her being there. She told Junger “I missed being that close to people, I missed being loved in that way”. So, shortly after recovering from her wounds, she made her way back to Sarajevo, leaving the almost idyllic surroundings of Italy for the death and destruction of her home.

There are more recent examples of this as well. The unity and all in this together attitude of the Ukrainian people in their fight against Russia has been well documented, civilians and soldiers of all classes and backgrounds have come together as one country. I spoke to Mariam Naiem, a Ukrainian journalist, who since the start of the war has seen the effects on both herself and the people around her. “In war you start to care about each other a lot more, you start to value people a lot more. […] Somehow war makes everything crystal clear, in some ways I’m very ‘grateful’ for war because I started to understand my part in society”.

While millions of people have left Ukraine amidst a massive refugee crisis, that hasn’t stopped hundreds of expat Ukrainians returning to their birthplace. Similar to Sarajevo and Ahmetasevic, many people don’t want to be on the side-lines, and they’re willing to give up lives of relative luxury for a warzone. Naiem thinks that the sense of community felt is a huge draw “I think this is one reason that Ukrainians want to go back to Ukraine, because there is a lot of pros to be out of the country like you won’t be killed by a Russian bomb [sic], but everyone wants to go back, think of it like you’re outside on a cold day and you want to go back to your warm blanket. Ukraine is that warm blanket”.

It isn’t just full-scale warzones where people can experience so much peace and purpose during destruction. An Irish psychologist named H.A. Lyons found that suicide rates in Belfast dropped 50 per cent during the riots of 1969 and 1970, while homicide and other violent crimes also went down. Depression rates for both men and women declined abruptly during that period with men experiencing the most extreme drop in the most violent districts. While County Derry on the other hand which saw almost no violence at all, saw depression rates rise. In his 1979 journal of Psychosomatic research Lyons states “When people are actively engaged in a cause their lives had more purpose… with a resulting improvement in mental health”.

Maybe that’s why people can find such a “relief” during wartime, it provides a break from the stresses and reality of the systems we have built around us.

Looking at these examples you begin to realise the appeal and almost psychological benefits of war. Community is a stalwart human necessity which helped us evolve into the most advanced species planet Earth has ever known, community is what helps people get through the toughest of times by knowing they don’t have to go through it alone, community is how uncontacted tribes have survived thousands of years without what Westerners would class as basic human necessities. And during war, community is never felt stronger.

Although these ‘benefits’ of war should probably be looked at less as the positives to take away from war and more used to highlight some of the increasingly growing social and cultural problems in Western society; Ahmetasevic was very clear about this during her interview “Whatever I say about the war I still hate it. […] I believe that the world we are living in and the peace that we have, is very fucked up if somebody is missing war. And many people do”. It’s a tragedy of our modern culture that some people so lack in community that they seek out active warzones just to feel a scintilla of support.

Life in Western societies can be a very lonely place, to quote the rapper Dave; “we’re all alone in this together” perfectly sums up how despite the growing number of people living in denser and denser populated areas, people can still feel more alone than ever. Cultures and societies have put so much emphasis on the individual and the self, which no doubt has benefits when it comes to success and individuality, but have forgotten the importance of human interaction, not on social media, not in a metaverse, but raw, in-person human cooperation. Evidence shows that depression and loneliness are closely linked, especially in people over the age of 50, with almost one in five cases of depression linked to people suffering from loneliness the previous year. Loneliness not only varies by age but also by gender, men over the age of 60 who are living with a spouse spend almost double the amount of time alone than said spouse. Men of the same age bracket living alone averaged 43 per cent of their waking hours alone compared to 34 per cent for women.

Maybe that’s why people can find such a “relief” during wartime, it provides a break from the stresses and reality of the systems we have built around us. Systems that have helped create some of mankind’s greatest advancements, systems that have provided unparalleled food and water security, systems that have allowed humans more comforts in life than their ancestors ever could have dreamed of, but systems that are isolating, relentless, and sometimes mentally unrewarding. Systems that have people trapped in glass cages, sitting at desks for eight hours a day working for next month’s rent, next month’s food, next month’s dream. Humans can spend half their existence grinding a job they hate that they begin to struggle to tell the difference between life and work. The only system in war is survival, and this primal instinct can help simplify matters and re-align one’s values. People no longer worry about paying for their Netflix subscription or their new watch, as there is only the self and others to care for. Rupi Kaur once wrote about community that:

If we’re present to take part in your happiness

When your circumstances are great

We are more then capable

Of sharing your pain

This echoes never louder than in war, and maybe peacetime could take a hint from it too.

War is not the answer.

War is not the solution.

War is not the way forward.

But war can fill a hole in people’s lives. It can give them meaning and purpose in an increasingly confusing world.

War is kill or be killed.

War is die or survive.

War is win or lose.

War isn’t filled with taxes, office parties and boring 9-5 jobs. War isn’t working out what to wear for a siblings wedding or a first date.

War is a simple, binary kind of existence, never being able to worry about the future, only thinking about the present. And there’s a kind of harmony to that.

Written by

Isaac YielderJournalist interested in a wide scope of topics, ranging from wars to religion, cartels to culture.

Read next

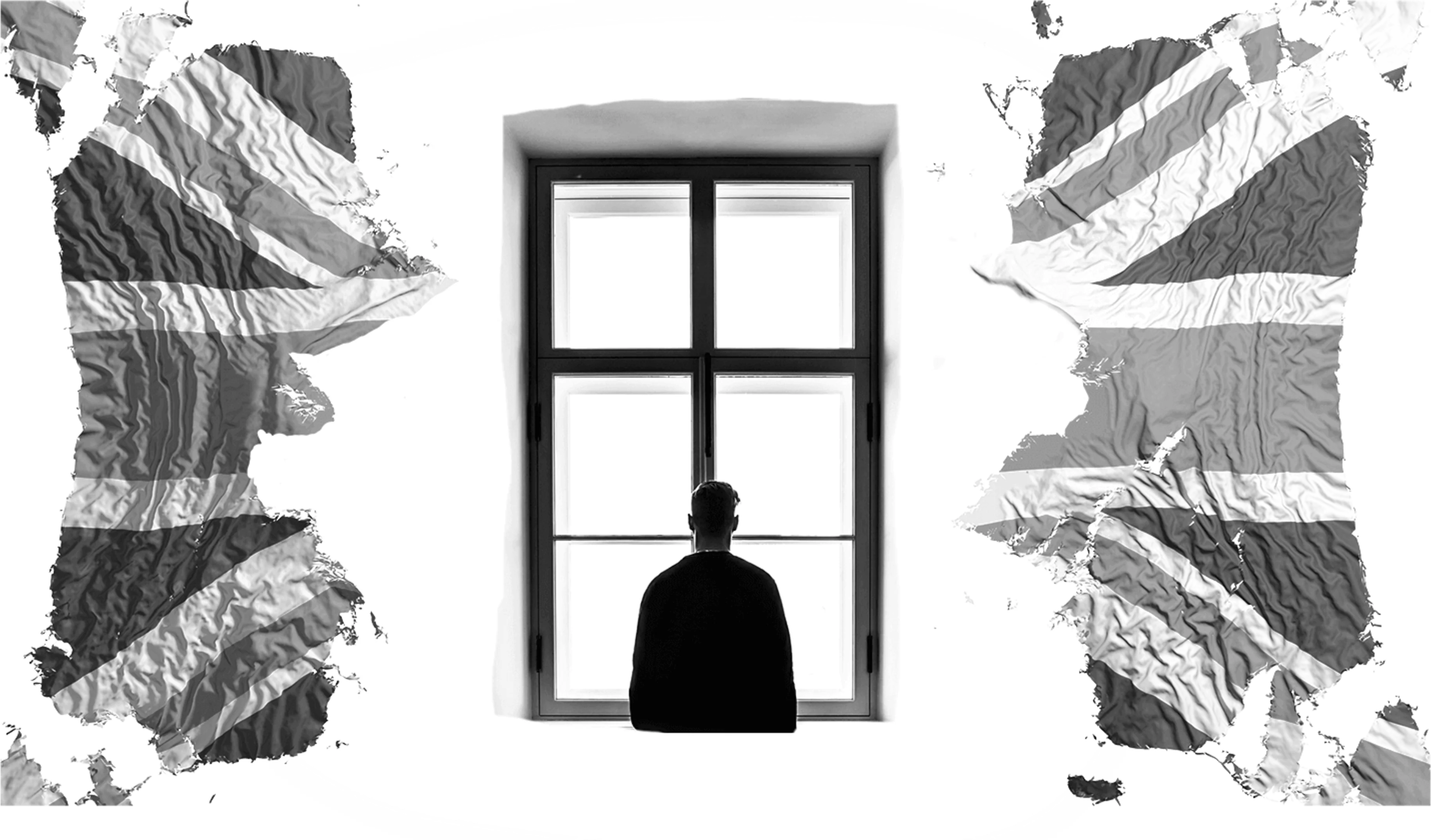

Lonely Britain: the death of the church has killed our community

Connor McIntyre

The 'Working from Home' Mistake

Linden Grigg

Brexited, Bored and Broken: how Britain is losing its communities

Sean Ryan

Weekly emails

Get more from Isaac

The Fledger was born out of a deep-seated belief in the power of young voices. Get relevant views on topics you care about direct to your inbox each week.

Write at The Fledger

Disagree with Isaac?

Have an article in mind? The Fledger is open to voices from all backgrounds. Get in touch and give your words flight.

Write the Contrast