T.S. Eliot quipped that humankind cannot bear too much reality, but in the last month some of Britain’s most powerful institutions have fully embraced a fantasy realm. The death of Queen Elizabeth II saw broadcasters, columnists and politicians compete in an Olympics of obsequious tribute. Whilst a period of mourning and reflection may have been appropriate, it became impossible to question the automatic succession of King Charles, the wall-to-wall media coverage, or the rationale for suspending government in a cost-of-living crisis. Organisations from Center Parcs to the Football Association ensnared themselves in this atmosphere of febrile deference. After the Queen’s funeral came the one-month Chancellor, Kwasi Kwarteng, with his so-called “mini budget”: an unapologetic handout to the top percentile against the interests of the other 99. No amount of spin could disguise a tax bonfire for the rich in pursuit of economic growth that could only benefit them. The public, the gilt markets and - mercifully - the Bank of England, reacted accordingly. Kwarteng was sacked on Friday, but more than symbolic damage has been done.

While for most Britons, news of the Queen’s death and Kwarteng’s budget saw opposite reactions, we should not view them as unconnected phenomena. They are both symptoms of a chronic classism that permeates British public life. Social class has dominated British conceptions of identity for centuries, from matters of consumption and manners, to education and occupation. But regardless of how we taxonomise a class system, the forces of inherited and extreme wealth, bolstered by willing agents in politics and the media, rise to the top. Monarchy is the ultimate example of blood-based privilege, and how that institution is treated during landmark moments - with reverence to a fault, it seems - reminds us that classism is alive and well. So does a budget, on 23rd September, that no amount of government-spin could paint as tackling economic inequality. Hours after announcing his market-spooking measures, Chancellor Kwarteng attended a drinks party at the home of a congratulatory hedge fund manager in a demonstration of his true political loyalties - and the revolving door between the highest echelons of finance and the modern Conservative party.

We are nearing a winter of spiralling inflation, fuel shortages, and mortgage oblivion inflicted by the governing party’s own experiment. The Labour party, under the increasingly confident leadership of Keir Starmer, is primed to benefit but trapped in a system that provides no ejection mechanism for Liz Truss - or the next Prime Minister on the Tory carousel - until late 2024. There is an urgent case for constitutional reform, and that must address monarchy as a primary edifice of British classism. The Queen’s death revealed again how much the institution commands a slavish attitude not only from right-leaning tabloids but our most trusted national broadcasters. Monarchy and the proposed beneficiaries of September’s mini-budget are two sides of a coin of wealth and power, concentrated in the hands of a tiny minority to the detriment of the rest.

As long as the Queen was alive, I was happy to view monarchy as a benign national soap opera. Martin Amis argued that it ‘allows us to take a holiday from reason; and on that holiday we do no harm’. Yet in the days after September 8th, every television channel demanded I doff my cap, and even The Guardian filled edition after edition with increasingly banal tributes. Thus I newly considered the institution’s more nefarious side; to further Amis’s metaphor, our holiday’s harm lies in the emissions of the flight or litter strewn on the beaches. On the day of the Queen’s death, BBC anchor Clive Myrie described the energy bills crisis as ‘insignificant’ compared to Her Majesty’s health: a sloppy word choice after hours of presenting, I’m sure, but a comment which fittingly characterised the copy of many journalists in the days that followed. Meanwhile, Scottish police manhandled anti-monarchy protestors who dared heckle Prince Andrew. Broadcasters interviewed a woman who visited the Queen’s casket in Edinburgh seven times but ignored individuals missing cancer screenings or pregnancy check-ups that the NHS cancelled to commemorate the day of her funeral. Throughout the 10-day mourning period, government business played second fiddle to a 96-year-old who died in considerable comfort. There could be few greater demonstrations of the toxicity of class deference in the UK.

I, like so many, admired the Queen’s exemplary commitment to work and service. However, it seems that in restricting herself to those values, Elizabeth II permitted our national nostalgia for an era of repressive class conformity to shine through. Born in 1926, she was a portal to the Downton Abbey - cum - National Trust glamorisation of landed aristocrats above, with the rest of us below: seen, but not heard. The Queue to view her coffin in Westminster Hall indulged that archaism. While I have no qualm that people would want to make a patient pilgrimage to pay their respects, media outlets again valorised the practice of waiting for up to 18 hours in often cold, autumnal conditions. This benefitted those with the time and means to travel, in the place of a more egalitarian ballot. We saw The Queue’s classism writ large when This Morning presenters Philip Schofield and Holly Willoughby were alleged to have pushed in line, ignoring the fact that all Members of Parliament and invited guests had a right to do so. As Boris Johnson demonstrated so adeptly during lockdown, it was one rule for them, and another for us: Phil and Holly were merely unfortunate enough to be deemed on the wrong side of the class divide.

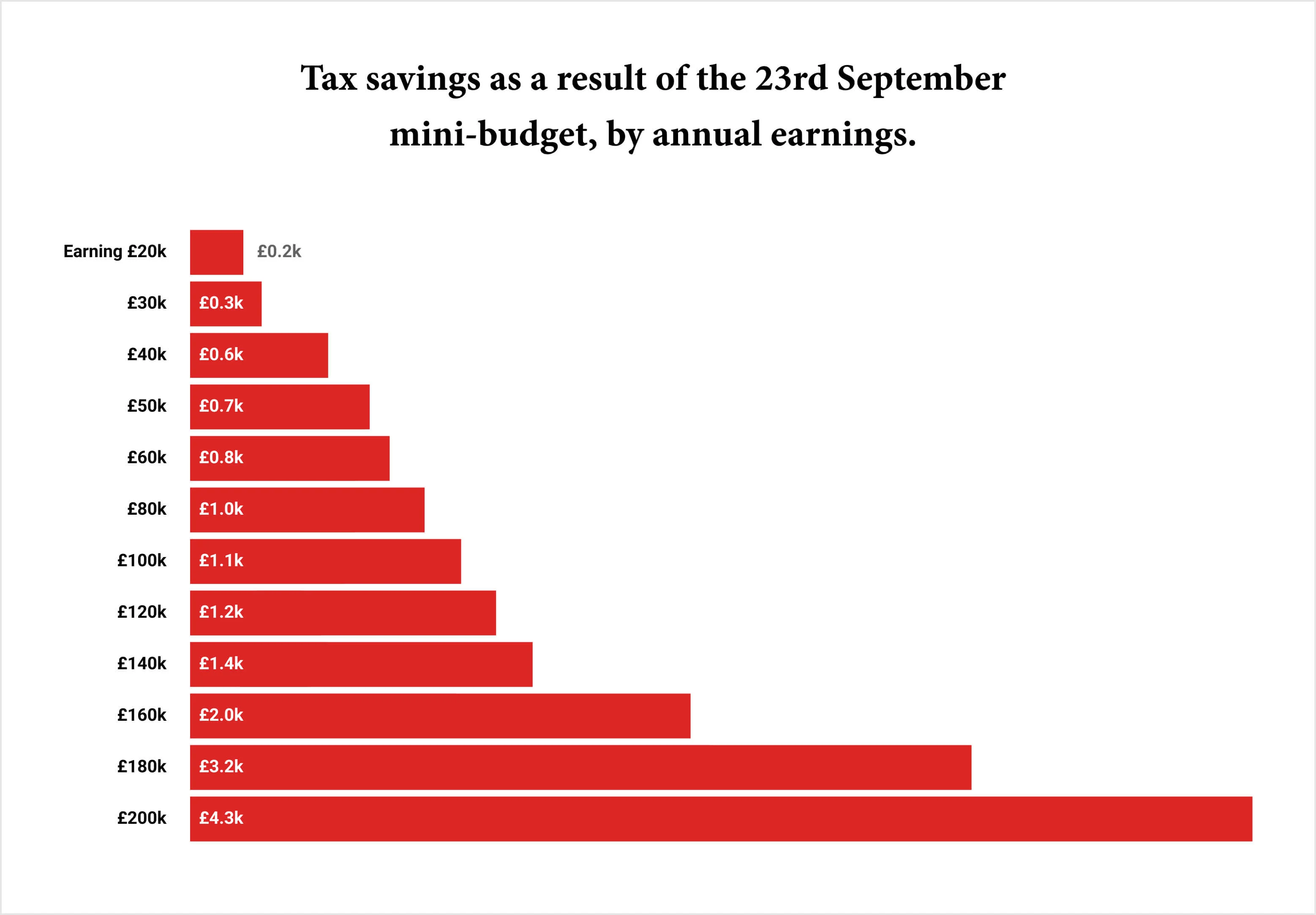

Absent the genuine grief that precipitated this monarchy-based class reminder, Kwasi Kwarteng’s mini-budget saw a much more adverse public reaction which eventually precipitated his downfall after just 38 days in the job. To lift the cap on bankers’ bonuses would obviously benefit the extremely rich, alongside the abolition of the top 45% rate of income tax. The above estimate shows that those with annual salaries of £200,000 or more - the top 1% of earners - will be £4,300 better off after the mini-budget, while those on £20,000 - the 70th percentile - will see just £200 in savings. This elite economic class will also suffer the least from the raising of the energy price cap, at £2,500 for the average household. Kwarteng’s intervention was that of an ideologue who wants to transform Britain into a low regulation, high productivity finance hub: “Singapore-on-Thames”. There are myriad reasons this could never work: the UK is ten times more populous than the city-state of Singapore, for one. And this post-Brexit mirage is pursued by ideologues in Truss, Kwarteng, and now the new Chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, who proposed the greatest corporation tax cuts of any contender in the recent Tory leadership contest. They are squirrelled away from the problems of most Britons, strategising with the exuberant abandon of a teenage gamer. The financial markets reacted to the budget by selling off British government bonds, known as gilts, spooking pension funds with considerable investment in these assets. A meltdown was avoided only by a Bank of England intervention to buy up £65bn in long-dated gilts, thus calming the markets. But this means that, in addition to pledging £43bn in tax cuts, the government will accrue greater borrowing debts to the tune of £12.5bn. Even if the mini-budget measures are reversed now that Kwarteng has been sacked, economic turmoil has been unleashed. For the new Chancellor to find the money to balance the books means real-term cuts to public services - Austerity 2.0 - which can only make the class divide that much wider.

Keir Starmer’s Labour party has reaped the rewards of this self-inflicted Tory crisis, racking up poll leads unseen since before Blair’s 1997 landslide. His party conference speech in Liverpool rejected economic division for statist solutions, most notably a nationalised “Great British Energy”. Yet Starmer has wholeheartedly embraced the monarchy side of the classism coin, with generous tributes to the late Queen and by instituting the National Anthem at Conference for the first time ever. This taps into the lingering respect for monarchy in the nation in a way that his predecessor, Jeremy Corbyn - whose influence Starmer has done so much to expunge from the party - never wished to muster. Having seen Corbyn’s republicanism branded as dangerously unpatriotic, Starmer’s position is probably somewhat cynical: aligning with a media which has always lionised the Royals.

Nonetheless, the monarchy will struggle to retain the reservoir of goodwill that King Charles garnered in the aftermath of the Queen’s death. The nature of the coronation will be his first challenge. It will be held on 6th May 2023 and be “shorter, smaller and less expensive” than his mother’s, 70 years before, given the ‘struggles felt by modern Britons’. This desire reflects Charles’ awareness of a monarchy reliant on public favour, but is a “slimmed down” ceremony possible? How can the ultimate display of class stability and continuity in Britain be anything but hallowed and opulent? Monarchy is a link from past to present, and - honourable as Charles’ intentions are - it will struggle to define its purpose in a deliberately diminished form.

Starmer’s Labour - with its 33% polling lead to play with - should maintain a healthy distance from the Palace, or else encourage such “slimming down”. This will be necessary if the party is to pursue constitutional reform to remedy the moral and intellectual void which has characterised our politics since Brexit, reaching its acme under Boris Johnson. The Liverpool conference approved a motion to institute a proportional electoral system; Starmer must accept and build on this to propose a written constitution, clearer powers for devolved assemblies and the English regions, and abolition of the House of Lords. With a more responsive system, the impulse to turn to monarchy as a symbol of unity won’t feel so necessary. I’m all for national cohesion and community, but I see a renewed imperative to base it on universal values and egalitarian institutions rather than the ultimate class-bound “Firm”.

While the Crown endures, entangled in our constitutional framework, there remains a licence for myopic media attention and a justification that individuals who have built their wealth through an accident of birth, timing, or reckless financial speculation are somehow deserving of reverence. Liz Truss’s dogmatic and chaotic government, which doesn’t pretend to serve any broad interest, is fundamentally better served by a King - eternal, unassailable - than a President. In the last month, it has become clear to me that if we are to tackle the class problem at the core of our society, we must solve a political dilemma and a monarchical one.

Weekly emails

Get more from Tom

The Fledger was born out of a deep-seated belief in the power of young voices. Get relevant views on topics you care about direct to your inbox each week.

Write at The Fledger

Disagree with Tom?

Have an article in mind? The Fledger is open to voices from all backgrounds. Get in touch and give your words flight.

Write the Contrast