I half-promise to improve my diet every other week. Guilt-ridden by the latest spate of takeaways or a hearty roast dinner, I’m prone to proudly rustle up a colourful salad, only to return - appetite unsatisfied - to the biscuit cupboard a few hours later. It doesn’t help that food culture is a minefield of mixed messages. To diet, or to Deliveroo? A 2017 BMJ study found that nearly 30 times as much money is devoted to junk food advertising than the UK government spends promoting healthy products. Meanwhile, many individuals swear by supplements as miracle cures, alongside a telephone directory of 5:2, keto, and paleo diets. One can even pay $10,000 for an 11-night cleansing and detox yoga retreat in Thailand, with the option of a pure water fast to eliminate "negativities and pollutants".

Such unsustainable, pseudo-scientific nonsense fuels disordered eating and has multinational conglomerates rubbing their hands together with glee. The 10 largest food companies made profits in excess of $100 billion in 2018 by pumping their products full of chemical stimulants to leave us hungry for more. It is by design that over two-thirds of American adults, and 64% of their British counterparts, are medically overweight or obese. At the other end of the scale, the NHS Confederation reported last year that referrals for children with eating disorders were "through the roof". How do young people, trapped in a social media comparison bubble, even begin to make healthy diet choices?

The answer - to coin a phrase - is education, education, education. Fallacies about fat, vitamins, food labelling, and even exercise have been exposed by recent scientific breakthroughs. Several weeks ago, sleep-deprived after an evening of heavy snacking and the acute nocturnal indigestion that followed, I listened to a podcast with the nutrition expert, Professor Tim Spector. As co-founder of the ZOE food study, his day job is to myth-bust the "dangerously inaccurate" information that comprises much-established wisdom about nutrition. Spector explains how the composition of our gut microbiome - the collective term for the microbes that inhabit our digestive tracts - influences everything from short-term energy levels to longer-term indicators like sleep quality and mood. The problem is that much government and even NHS advice is struggling to keep up with this rapidly accelerating science.

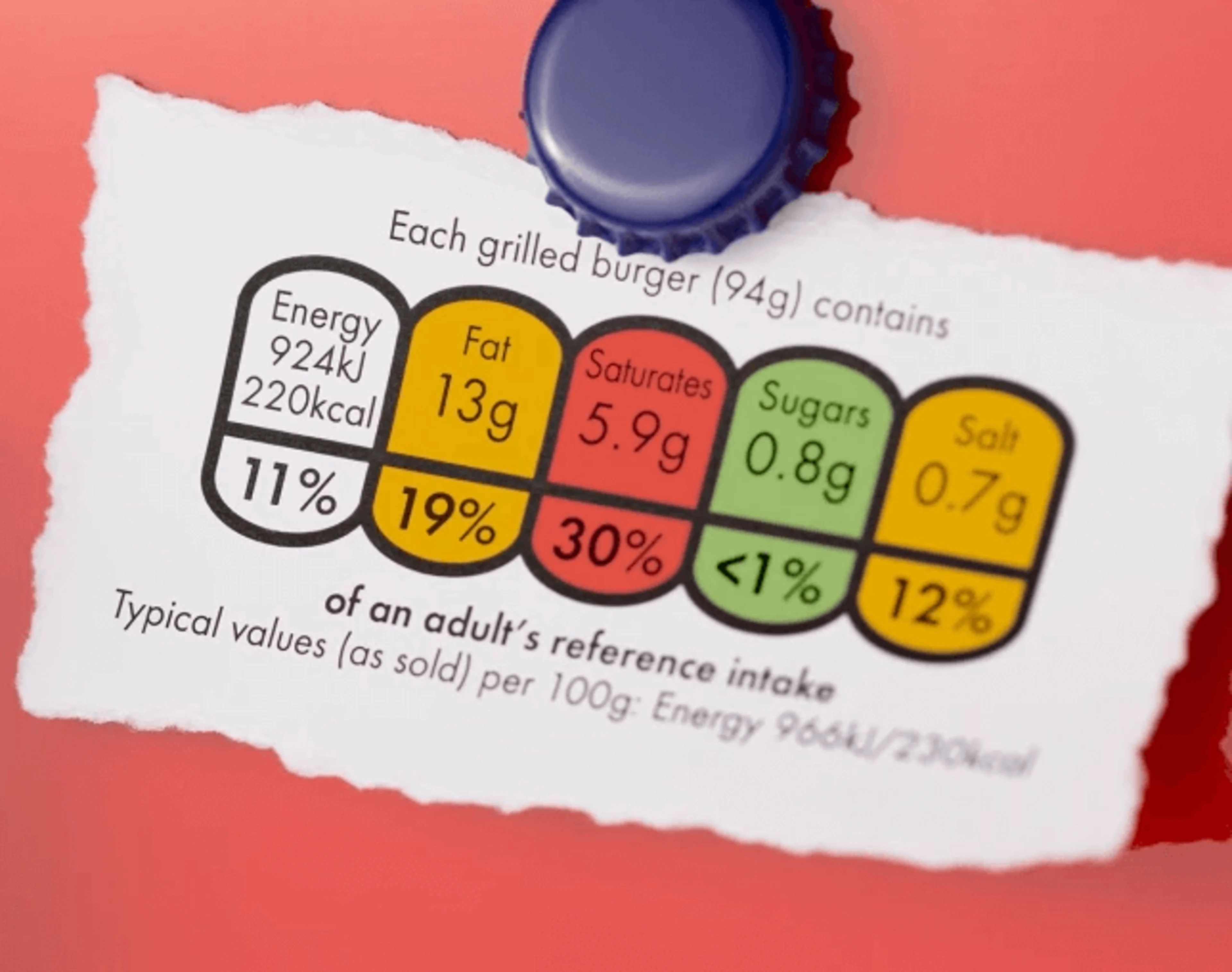

To take one prominent example, we are surrounded by calories: from “traffic light” indicators on packaged foodstuffs to the newly-introduced counts on British restaurant menus. But the fact is, as Spector elucidates in his excellent book Spoon-Fed, that a calorie is a meaningless indicator of what health benefit a foodstuff will give someone. Myopic focus on the calorie feeds into our yearning for control but is illogical when applied to actual people. A woman of 6 foot will be told she needs 2000 calories a day, while a man of 5 foot 6 is advised to eat 2500. Go figure. “Recommended Daily Allowances” neatly classify sugars, fats and salt as if these are monolithic categories worth measuring. But a quick comparison between an ultra-processed if allegedly “low fat” American diet of ready meals and Diet Coke, versus a Mediterranean offering rich in oils, breads, cheeses and red wine, confirms these are poor indicators of health and quality of life.

Beyond calories, further research has transformed my attitude toward several foods and practices. I have often guiltily eschewed breakfast, only to find that food science is far more forgiving of personal preferences than the “most important meal” mantra. The important thing is to restrict meals to a 12-hour period - say 8am to 8pm - to allow your gut to rest and recover as you would any other major organ. Spector discards another cardinal rule in “five fruits and vegetables a day”, replacing this with “as many as you can manage”. We should aim for a diet rich in vegetables, seeds, nuts, spices and fruits of all colours, since they are rich in polyphenols. These “good” bacteria stimulate the gut microbiome into an intricate tapestry. The same is true of probiotics: fermented foods like yoghurts, kombuchas and sauerkraut.

To boost polyphenols we must avoid “ultra-processed” foods. You can spot these from their long lists of increasingly dubious ingredients. They might appear healthy, but are filled with chemicals to boost shelf-life, taste or shape. I was stunned to read that between 50-70% of daily calories in the UK and the US are consumed in ultra-processed form, from the seemingly innocuous seeded loaf to a supermarket lasagne or a carton of orange juice from concentrate. These are different from plain “processed” foods - milk, or dried and tinned products - and the main enemy for anyone striving to eat more healthily.

The food myth I’ve fallen for most egregiously is that you can eat whatever you like as long as you exercise. I’ve used a run or a cycle as psychological justification for all manner of overeating: the achievable goal of 10,000 daily steps seems like a simple ticket to “burning off” calories and fat stores. I’m clearly not alone - First Lady Michelle Obama’s “Let’s Move” campaign to tackle obesity among American schoolchildren followed a similar logic. But the body has a defence mechanism against using exercise to shed weight. If you work out without taking on extra energy, your metabolism will slow, you will feel hungrier and tire easily. I experienced this last week when resolving to run 10 kilometres home from work instead of a more direct 5. I got home and made two portions of curry: one for dinner, one for lunch the next day. You can count on one hand the number of minutes between my scoffing of each portion.

Eating better is a slow, experimental process, determined by individual metabolisms as much as general precepts. So far, I have restricted my snacking by buying as few as possible: crisps and biscuits being my great weakness. I’m eating more fruit, vegetables and pulses, often motivated by rapidly approaching use-by dates; my foray into probiotics had me ID’d at Sainsbury’s for accidentally buying a kombucha with CBD. I’ve spent weeks deciphering what irritates my gut, and resolved to avoid the starchy panini and fruit smoothie combination that contributed to my post-lunch energy slump. Finally, I’m trying to cook more from scratch - using liberal quantities of olive oil after the revelation that it’s healthy - and to avoid ultra-processed supermarket meals.

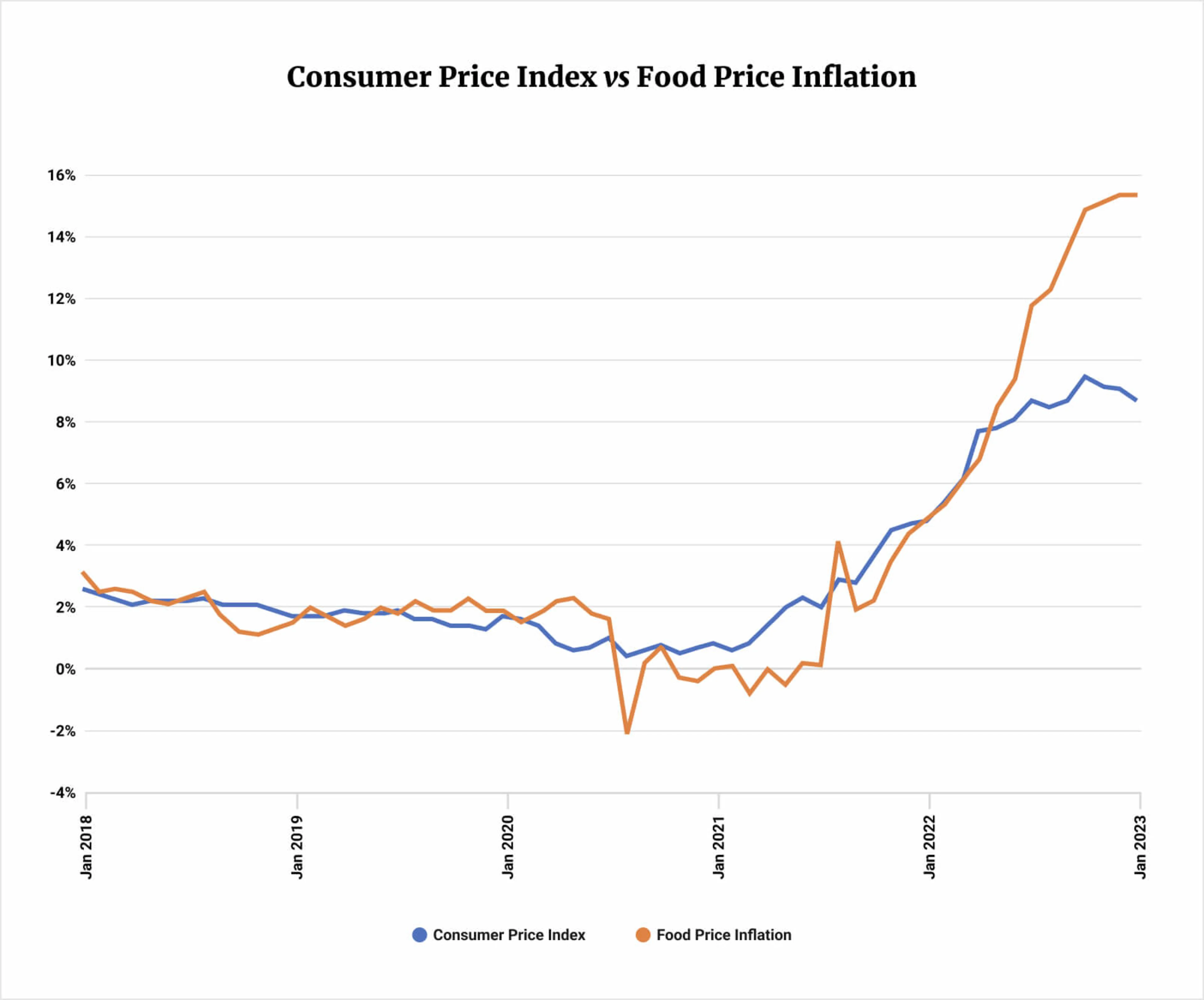

Overhauling an entrenched diet, however, requires a considerable devotion of time and money to be long-lasting. What for me might be classed as a food rut - eating the same unhealthy lunch continuously - may be a deliberate decision for an individual on a tight budget. And where is the impetus to change? I vividly remember visiting a Walmart store in the US where an 8-piece fried chicken box cost less than a freshly-prepared fruit salad. So long as the food industry supports the cheap and easy consumption of ultra-processed foods compared to plants, then the ecosystem of junk foods, fad diets and disordered eating will remain. If anything, the gulf in price will grow; the broadcaster-turned-farmer Jeremy Clarkson has advocated that prices in the UK for farmed goods should be doubled on account of the ‘soul-destroying’ toil that goes into their production. Amid a cost-of-living crisis, with food prices rising 16.5% in the 12 months to November 2022, any drive to reduce the cost of nutrient-rich plant foods would place intolerable pressure on the agricultural sector. Government subsidy could be an option, but it’s hard to see healthy foods ever competing in the marketplace with junk brands whose nutrient-deficient content is the very reason for their low price.

It’s remarkable to think that for 25 years, my knowledge about the food which has kept me alive has been rudimentary at best - false at worst. Nutrition science should be mandatory teaching in schools. We are taught the value of physical education at an early age, yet even by Year 6, a stunning 23.4% of British children were obese in 2021-22. Dietary change is the missing ingredient. It’s a daunting task, especially when it requires decoupling from the lodestars of received wisdom in calories or daily allowances. I’d recommend that anyone read Tim Spector’s Spoon-Fed, which breaks down the vital precepts into a 12-point plan. Many of these require minimal effort or financial means. And some of the book’s 23 chapters - each a food myth debunked - will be applicable to all. Coffee drinkers will be pleased to hear of its benefits for digestion; alcohol lovers that a glass of red each night will be welcomed by your gut microbes.

The main lesson is to think more critically about the food we buy: its source, the number of ingredients, its sustainability, and its impact on our individual gut microbiomes once consumed. If we treat gut health with the attention it deserves - on a par with physical and mental health - we will lead happier, more vibrant lives.

Written by

Matt JeffordUniversity administrator and pub quiz enthusiast. I'm engrossed by current affairs, reading, tennis and food, and an expert in poor political predictions.

Read next

Weekly emails

Get more from Matt

The Fledger was born out of a deep-seated belief in the power of young voices. Get relevant views on topics you care about direct to your inbox each week.

Write at The Fledger

Disagree with Matt?

Have an article in mind? The Fledger is open to voices from all backgrounds. Get in touch and give your words flight.

Write the Contrast